The book Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What It Says About Us) by Tom Vanderbilt was published a decade ago at this point. And since it includes extensive discussion of technology like autonomous vehicles and instrumented driving, some may be inclined to pass it over as too dated, but it has some key perspectives to offer. The second chapter in particular combines information about psychology and some then-recent studies of new drivers getting feedback on their driving for some really striking insights.

The crux of the chapter focuses on how the experience of regular driving, in the absence of mishaps, creates a false sense of security, competence, and even expertise in all of us. Vanderbilt notes that most of us, most of the time, manage to get in our vehicles, traverse our routes, and get out without causing or even encountering any "accidents." He points out that this can create a mistaken impression that we are very good drivers -- after all, we haven't died in a crash yet. But what is missing is an awareness of our lack of awareness. We are only aware of the very coarse-grained feedback that we survived. We do not know about all the incidental near misses we engendered or were in the presence of unaware along the way. Using the example of research in workplace accidents, he cites a ratio of injury accidents to fatal accidents of about 30 to 1. And then a further relationship of near misses to injury accidents of about 10 to 1. So roughly for every fatal accident, there are approximately 300 near misses (obviously of varying severity). If we think about the reality that there are around 40k deaths in car crashes each year, that translates to 12M near misses in a year. If half the country's population are active drivers, that means we each have about a 6% chance of owning one of those near misses. Now think about how we really aren't all above average, as we seem to think. So some of us may own much more than that 6%. And then think about how many other drivers you interact with on any given day in terms of how many of those near misses that you don't "own" might nevertheless be in your immediate vicinity. You are probably starting to get the idea... 1) We don't get the feedback we need under normal circumstances to actually understand whether we are driving well or not; and 2) Not understanding one's own level of hazard is itself a form of risk.

Interestingly, technology can start to counteract some of this. Not just by making all vehicles driverless, but rather by using much of the instrumentation technology that makes autonomous vehicles possible to present human drivers with realistic feedback about their own performance. We are all familiar with the concept of the black box flight recorders in planes. We are now in a position to have similar devices in cars. It does require fairly extensive kitting out, with front, rear, and interior cameras as well as algorithms to scrape data from other onboard systems and possibly independent measurement devices like accelerometers. Those devices can pinpoint when the braking was too abrupt, when obstacles or other road users were too proximate, or when attention flagged. They can provide a log to drivers.

In one example cited, new, young drivers in Iowa (where 14 year olds can get their licenses and then proceed to careen around on ultra dangerous rural highways) were given scores for their performance. This turned into an almost unintended "gamification" of driving for them. As one participant noted, he "figured out" how to increase his score by looking further ahead, breaking sooner, and anticipating what would be happening. He was very happy with his improved standing, having beat the system. But we should all be thrilled that he basically learned how to drive better in the process of gaming.

In essence this is a version of the Dunning-Kruger effect in which people who know the least or are least capable also are poorly equipped to assess their level of knowledge or ability and wind up overestimating their capacity. It's an excellent corrective to the autopilot we tend to slip into with habitual practices like driving. And it's something we can work to counteract in our own lives, recognizing always that we are perhaps not getting the key pieces of feedback on our performances we need.

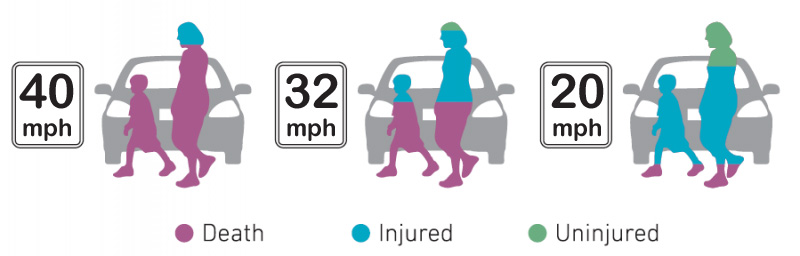

Driving is one of the riskiest activities we engage in on a routine basis. We need to maintain our awareness of that hazard in order to keep ourselves and all those around us safer.