How do you instill love of the earth and a conservation ethic in children? More and more research is pointing to kids’ need for free play and exploration in a natural setting to develop a long-lasting personal affinity for nature. More specifically, it seems that children need frequent, spontaneous, unscheduled, unscripted, self-directed opportunities to play in nature to really get it. There are other factors that promote love of nature, including, in order of diminishing effectiveness, mentors or parents modeling favorable attitudes, participation in outdoor groups like scouts, negative environmental experiences (e.g. the loss of a favorite play site to development), and last, environmental education as currently practiced (e.g. school trips to nature centers for educational programs).

So, let’s all head for the woods! Or at least out into a field...

While that may seem easy enough to accomplish, now that the need is becoming clear, there are already warning bells ringing about what we may have wrought in the minds of many young adults. Almost no one under the age of 35 has had such opportunities, especially kids in cities, but even in semi-bucolic places like central PA. Instead, they have countless artificial experiences on playing fields and amped-up expectations from media portrayals of nature that make them fairly indifferent to the subtle pleasures of the real thing. It doesn’t help that the litany of parental fears -- of uv radiation, of bugs, of pesticides, of traffic, of pollutants, of physical injury, of boogeymen -- are at least to a certain extent justified. It’s just not as easy a decision to let children roam free from the end of the school day until dinnertime, much less for entire days on weekends and in the summer. Plus, we sabotage ourselves with endless homework and a junior-league rat race of enrichment with classes, tutoring and sports. The over-scheduling leaves little time for undervalued free time. We’ve also invented an array of new technologies to entice people back to the cave of the basement and away from the screen door, from video games to the internet. It’s hard for mere rocks and dirt to compete, especially in the absence of substantial marketing to gain mindshare. And, for the few kids afforded the time, the inclination, and the opportunity to roam, it’s a fairly lonely world out there, with all their potential playmates under lock-down or in transit.

Many of these ideas have filtered into the general media, ever since the 2005 publication of The Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder, by Richard Louv. Articles and programs have appeared from the New York Times to the Wall Street Journal. Even the Daily Item’s columnists may conjured it up in relation to childhood obesity or other public health issues. Over 10 years ago, working up to their conference in Wilkes-Barre entitled “No Child Left Inside,” the Pennsylvania Association of Environmental Educators hosted three lectures by an educator named Ken Finch from a group called Green Hearts Institute for Nature in Childhood, out of Nebraska. The second lecture took place at Penn Tech in Williamsport. Finch was an environmental educator for over three decades, including as a teacher, a nature center director, and eventually as a promoter of child-appropriate landscaping and nature preschools. In addition to outlining this nature-deficit syndrome, both Louv and Finch point to the larger costs: alienation from the earth, a lack of wonder for the power, beauty and structure of the natural world, and an absence of personal connection to land and to place. All of these contribute to viewing the world as just a source or a sink, something to be mined, worked, and dumped on without a whole lot of reflection or comprehension.

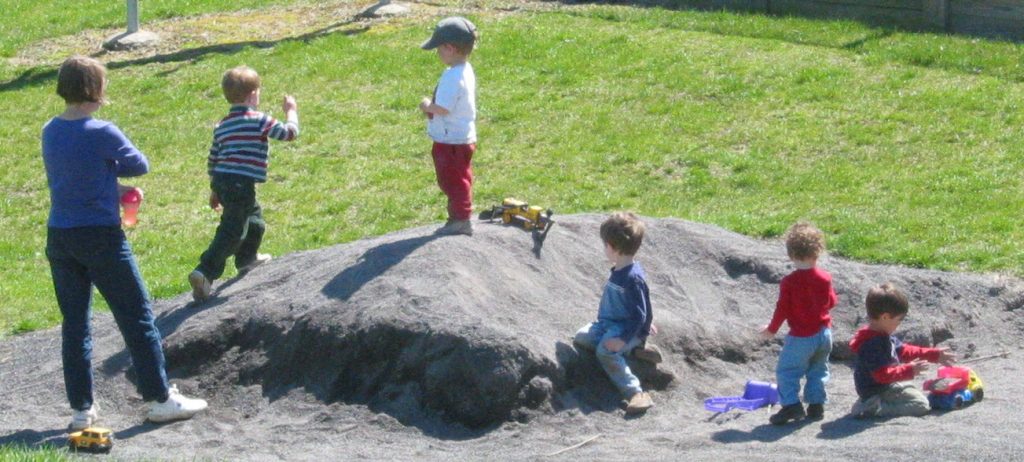

On the one hand, these ideas can and do serve as a wake-up call to parents, clearly pointing to the need for more active lifestyle in childhood and more proactive parenting as far as focusing on activities, like wading in a stream or digging for worms, that may not be covered in other parts of kids’ lives. Lewisburg was once home to informal nature playgroups, hosted Nature's Cool for a few years, and now has a Nature Preschool program offered by BVRA. Both the former standing playdates and the new preschool program are not as spontaneous as they could be (in comparison to the free-range children of yore), but they do allow for pick-up seed-pod play, horsing around in a wagon, and appreciation of the glories of the mud kitchen. While there are lots of interesting places, in-between spaces and hidey holes worth exploring in the Borough, kids are unlikely to find compadres there. If others are outside at all, they are far more likely to be on the default play site, on sterile, often plastic, and at times over-designed playground equipment, being warned away from the tantalizing glimpses of nature in the margins – downed tree limbs, a creek, the tall grass, a potential climbing tree.

According to the research, the window for establishing nature-leaning habits of mind and body is fairly narrow; we need to start ‘em young. Combine that with the ever-greater pressure toward academics in schools and it is clear that we can’t wait for education reform to solve the problem. Ken Finch’s take is to focus on bringing Waldkinder programs -- forest preschools in Germany and Scandinavia -- here. These programs are targeted at the usual preschool age-group offering extended open-ended group play opportunities in a safe outdoor setting with supervisors (think of them like dry-land lifeguards). Some programs like this have been around for decades. And they tend to be very popular. Educators take note, "Nature preschools also have an unusual strength within the non-profit sector: they can be financially self supporting once the facilities are constructed and opened." These programs take the kids outdoors in all weather. Depending on the state, that may mean, outdoors until the temperature drops below 20 degrees, like here in PA, or it may mean, outdoors until it goes below –20, as in the Great Lakes region. There is a learning curve and parents must be educated too – initially to see the fundamental merit of the concept and then, once the kids are enrolled, to make sure there are enough extra clothes on hand to see the minis through the mud, ice, wet and grit as the season dictates. Mittens -- lots of mittens -- are apparently key.

In working on bringing these concepts to fruition in the US, Finch splits his time talking to teachers, to parents, and to people in the nature center business. It was at a conference for this last that the original “aha” moment occurred. As he tells it, a group of nature center directors was sitting around relaxing at the end of the conference day, reflecting on all this data, when he suddenly said, “do any of you allow any of these things that ensure a strong bond between kids and nature in your nature centers?” The answer was no. The rules all say they can't climb trees, pick plants, dig, play with sticks, build forts, throw rocks in the water, or run around like wild things... And yet those are the things that kids need to do if they're going to be likely to want to patronize the center in the future. So they started talking about how to balance the danger of their sites being "loved to death" and the need for meaningful interaction on the children’s terms. One of the best things they hit on were nature play areas sited within the larger "do not touch" context. The fragility of the nature center could still be respected, but the need for connection could also be allowed and encouraged.

So parents are exhorted to clear space in their lives for nature; communities, to cooperate to establish opportunities and sites for it; educators, to develop preschool programs for it; and nature centers and public parks, to design it in. We are all also warned that what “it” is may not look like much to the untrained eye: packs of kids moving flock-like over a landscape, the productive work of sitting under a tree, and a good deal of being mean to ants. Louv and Finch both note that there seems to be a fair amount of creative destruction involved. If we can make room in our mature environmental ethic for such messiness, we will all reap the benefits later on. While many things are precious, there’s such a thing as being too precious about them. So at least consider making room in life, community and education programs for a bit of an ant-killing, bark-stripping, earth-disturbing free-for-all.

This is a re-release/updating of an article originally published in The Williamsport Guardian in 2007.